Tracing the Path of Current in a Simple Lighting Circuit

Tracing the Path of Current in a Circuit: A Guide for Electricians

For any licensed electrician, from a new apprentice to a seasoned journeyman electrician, mastering the ability to trace the path of current in a circuit is a fundamental skill. A proper understanding of how electricity flows is essential for installation, troubleshooting, and ensuring safety. At its core, the flow of electricity requires a complete path from the power source, through the load, and back to the source. This journey begins on a hot conductor, passes through switches and devices, and returns via the neutral conductor. Any break in this loop creates an open circuit, where current cannot flow, while an unintended connection, known as a short circuit, can cause dangerous overcurrent conditions. A solid grasp of the definition of electrical current and this path is the bedrock of all electrical work, from wiring a simple receptacle to diagnosing complex control systems.

Understanding the Fundamentals of Electrical Current

Before tracing a circuit, it’s crucial to understand the definition of electrical current. In simple terms, it is the flow of electric charge, carried by electrons, through a conductive path. For this flow to happen, three basic elements must be present: a power source (like a transformer or battery), a load (a device that consumes energy, like a light bulb), and conductors to connect them. To learn more about the physics behind this, you can explore this guide to electric charge and current.

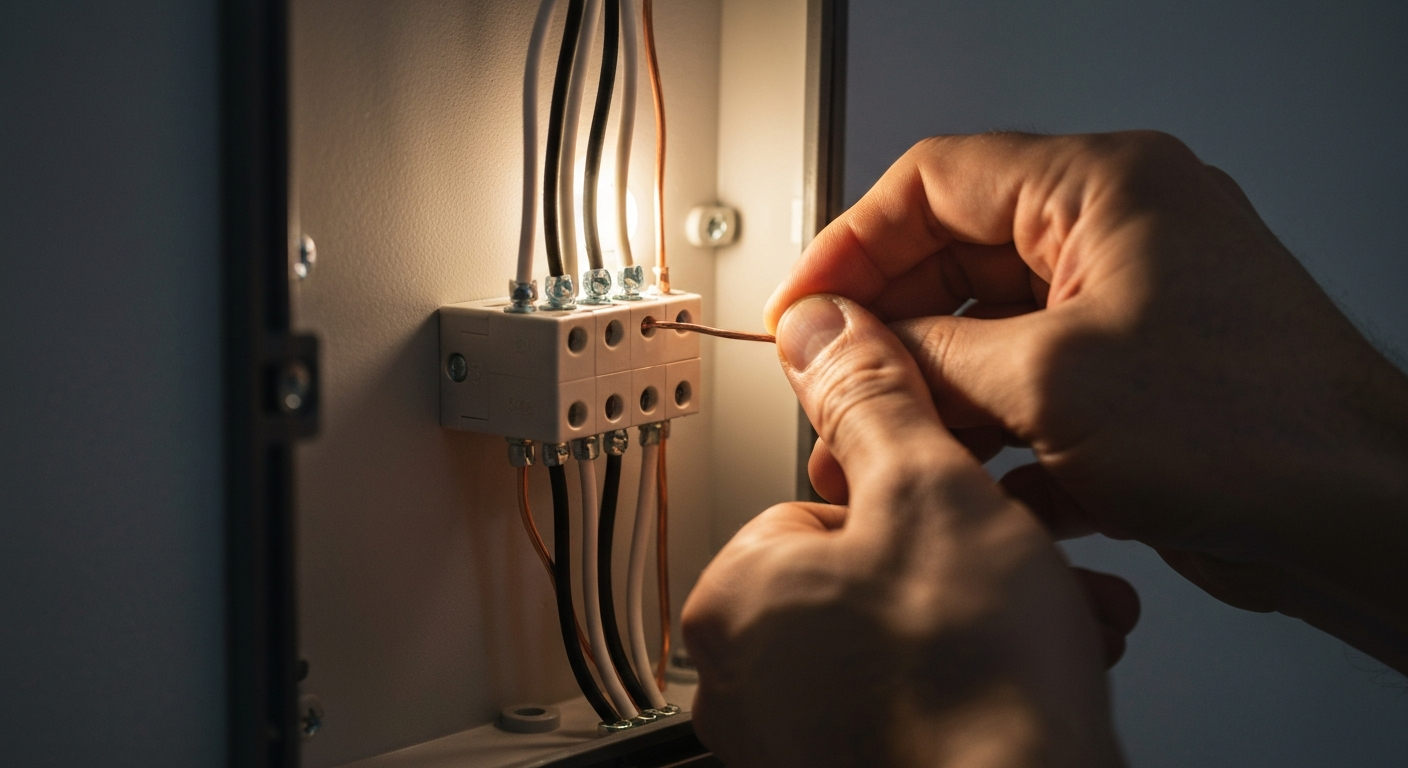

The conductors provide the roadway for the current. Materials that are good at this, like copper and aluminum, are known as conductors because they have free electrons that can be easily moved. You might ask, “what is a conductor?” It is any material that allows electrical current to pass through it with minimal resistance. This path has two distinct sides when connecting devices like switches or outlets: the line side, which is the portion of the circuit coming from the power source to the device, and the load side, which is the portion from the device toward the load. These terms are fundamental for correct wiring and are referenced in the context of equipment terminals throughout the National Electrical Code (NEC).

The Complete Path in a Simple Lighting Circuit

Let’s trace the path of current in a circuit using a standard residential lighting setup with a single pole switch.

- The Source: The journey begins at the main electrical panel, where a circuit breaker is connected to the utility’s power feed.

- The Hot Conductor: From the breaker, an energized wire, known as the hot conductor, carries the electrical potential. This wire, typically black or red in modern wiring, travels from the panel through the walls, often passing through a junction box, to the switch box.

- The Switch: Inside the switch box, the hot conductor connects to one of the terminals on the single pole switch. The switch acts as a gate. When it’s in the “ON” position, it closes the circuit, allowing current to flow through it. When “OFF,” it creates an intentional open circuit, breaking the path and stopping the current.

- To the Load: From the second terminal on the switch, another hot wire continues its path to the light fixture (the load). Here, the electrical energy is converted into light and heat.

- The Neutral Conductor: After passing through the filament of the bulb, the current must return to the source to create a complete path. It does this via the neutral conductor, a wire that is typically white. This conductor carries the current back through the circuit’s wiring to the neutral bus bar in the electrical panel, which is bonded to the ground, completing the loop.

It’s critical to properly understand the difference between the ‘hot’ and ‘neutral’ conductors. While the hot (ungrounded) wire brings the power, the neutral (grounded) conductor’s job is to return that power to the source. Both are essential for the circuit to function.

Troubleshooting Common Circuit Problems

When a circuit fails, the problem is almost always an open circuit, a short circuit, or a ground fault. Knowing how to diagnose these is a daily reality for a working electrician.

Identifying an Open Circuit

An open circuit is an incomplete path, which means current cannot flow. This is often caused by a loose connection at a terminal, a broken wire, or a faulty switch. The easiest way to find an open is by performing Continuity testing. With the circuit de-energized, a multimeter set to continuity mode can verify if there is an unbroken path between two points. An audible beep indicates a complete path, while silence indicates an open.

Dealing with a Short Circuit or Ground Fault

A short circuit occurs when the hot conductor touches the neutral conductor directly, creating an unintended path with very low resistance. This causes a massive surge in current that trips the circuit breaker. A ground fault is similar but occurs when a hot conductor touches a grounded object, like a metal box or the bare copper circuit protective conductor (equipment grounding conductor). Both situations are extremely dangerous and can cause fires or electrocution. Ground-Fault Circuit-Interrupters (GFCIs) are designed to detect ground faults, while Arc-Fault Circuit-Interrupters (AFCIs) are designed to detect hazardous arc faults; both types of devices quickly shut off power to prevent injury or fire.

Measuring Voltage Drop

Voltage drop is the reduction of voltage along a conductor due to its resistance. While some drop is unavoidable, excessive voltage drop can cause lights to dim and motors to run inefficiently. The NEC code book contains informational recommendations to promote reasonable efficiency. For example, NEC 210.19(A)(1) Informational Note No. 4 explains that a voltage drop of up to 3% at the farthest outlet of a branch circuit, and a total of 5% for the combined feeder and branch circuit, is acceptable. A multimeter can be used to measure the voltage at the source and at the load under load conditions; the difference between the two is the voltage drop.

Advanced Concepts: Series, Parallel, and 3-Way Switches

While a single light on a switch is a simple series circuit, many installations are more complex. Understanding the difference between a series vs parallel circuit is crucial. Most residential wiring uses parallel circuits, where each device receives the full circuit voltage.

Wiring a 3-Way Switch

A common complex circuit involves 3 way switch wiring, which allows a light to be controlled from two separate locations. This setup uses two special 3-way switches and an extra “traveler” wire. The hot feed goes to the “common” terminal of the first switch. Two traveler wires then run between the traveler terminals of the two switches. The common terminal of the second switch is then connected to the light fixture. Flipping either switch changes which traveler wire is energized, allowing the circuit to be opened or closed from either location. Per NEC 404.2(C), a neutral conductor must also be provided at each switch location to accommodate future use by devices like timers or smart switches, though it is not used in the basic switch operation itself.

Essential Tools for Tracing the Path of Current

A professional journeyman electrician relies on several key tools to accurately and safely trace circuits.

- Multimeter: This is the most versatile tool. It’s used for Continuity testing, measuring voltage, and checking resistance to diagnose issues like an open circuit or confirm a de-energized state.

- Circuit Tracer: For complex or undocumented wiring, a circuit tracer is invaluable. It consists of a transmitter that sends a signal down the wire and a receiver that audibly detects that signal, allowing you to trace a specific wire’s path through walls and ceilings and identify the correct breaker in a panel.

- Non-Contact Voltage Tester (NCVT): A quick and safe way to verify the presence of voltage in a wire or device without making direct contact. It’s an essential first-step tool for identifying a hot conductor before starting any work.

Step-by-Step Guide to Continuity Testing

Continuity testing is a foundational troubleshooting skill used to check for a complete electrical path. Here is how to perform the test safely with a digital multimeter:

- De-energize and Verify: Turn off the circuit breaker supplying power to the circuit you are testing. Use a voltage tester to confirm that there is no power present (see OSHA 1910.333(b)(2)(iv)(B)). This is a critical safety step.

- Set the Multimeter: Turn the multimeter dial to the continuity setting, often indicated by a symbol resembling sound waves or a diode.

- Test the Meter: Touch the tips of the two meter probes together. The meter should beep or show a reading close to zero ohms, confirming it’s working correctly.

- Test the Conductor: Place one probe at the beginning of the wire or path you want to test and the other probe at the end. For example, to test a switch, you would place one probe on each terminal screw.

- Interpret the Result: If the multimeter beeps, it indicates there is continuity, meaning you have a complete path. If it remains silent and the display reads “OL” (overload or open line), you have an open circuit, and there is a break in the path somewhere.

Primary Sources

- NFPA 70, National Electrical Code (NEC), 2023 Edition

- OSHA Standard 1910.333, Selection and use of work practices

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the primary path of current in a circuit for a standard light?

The primary path begins at the circuit breaker, travels along a hot conductor to a switch, through the switch (when on) to the light fixture (the load), and then returns to the electrical panel through the neutral conductor to form a complete path.

How does a short circuit differ from an open circuit?

An open circuit is an incomplete path where current cannot flow because of a break (like a cut wire or open switch). A short circuit is an unintended, low-resistance path between the hot and neutral wires, causing excessive current to flow and tripping the breaker.

What does the NEC code book say about voltage drop?

The NEC code book, in informational notes like NEC 210.19(A)(1) Informational Note No. 4, recommends limiting voltage drop to a maximum of 3% for a branch circuit and 5% for the total of the feeder and branch circuit to ensure efficient operation of equipment.

Why is a neutral conductor necessary for a complete path?

The neutral conductor is essential because it provides the return path for current to get back to the power source. Without this return trip, the electrons cannot flow continuously, and the circuit is incomplete or open.

Mastering these fundamental concepts is essential for any electrician. For those looking to deepen their knowledge and stay current with code changes, high-quality online electrical courses provide a valuable resource for career advancement.

Continuing Education by State

Select your state to view board-approved continuing education courses and requirements:

Disclaimer: The information provided in this educational content has been prepared with care to reflect current regulatory requirements for continuing education. However, licensing rules and regulations can vary by state and are subject to change. While we strive for accuracy, ExpertCE cannot guarantee that all details are complete or up to date at the time of reading. For the most current and authoritative information, always refer directly to your state’s official licensing board or regulatory agency.

NEC®, NFPA 70E®, NFPA 70®, and National Electrical Code® are registered trademarks of the National Fire Protection Association® (NFPA®)