What is Reactance? Inductive vs. Capacitive Reactance Explained

What is Reactance? Inductive vs. Capacitive Reactance Explained

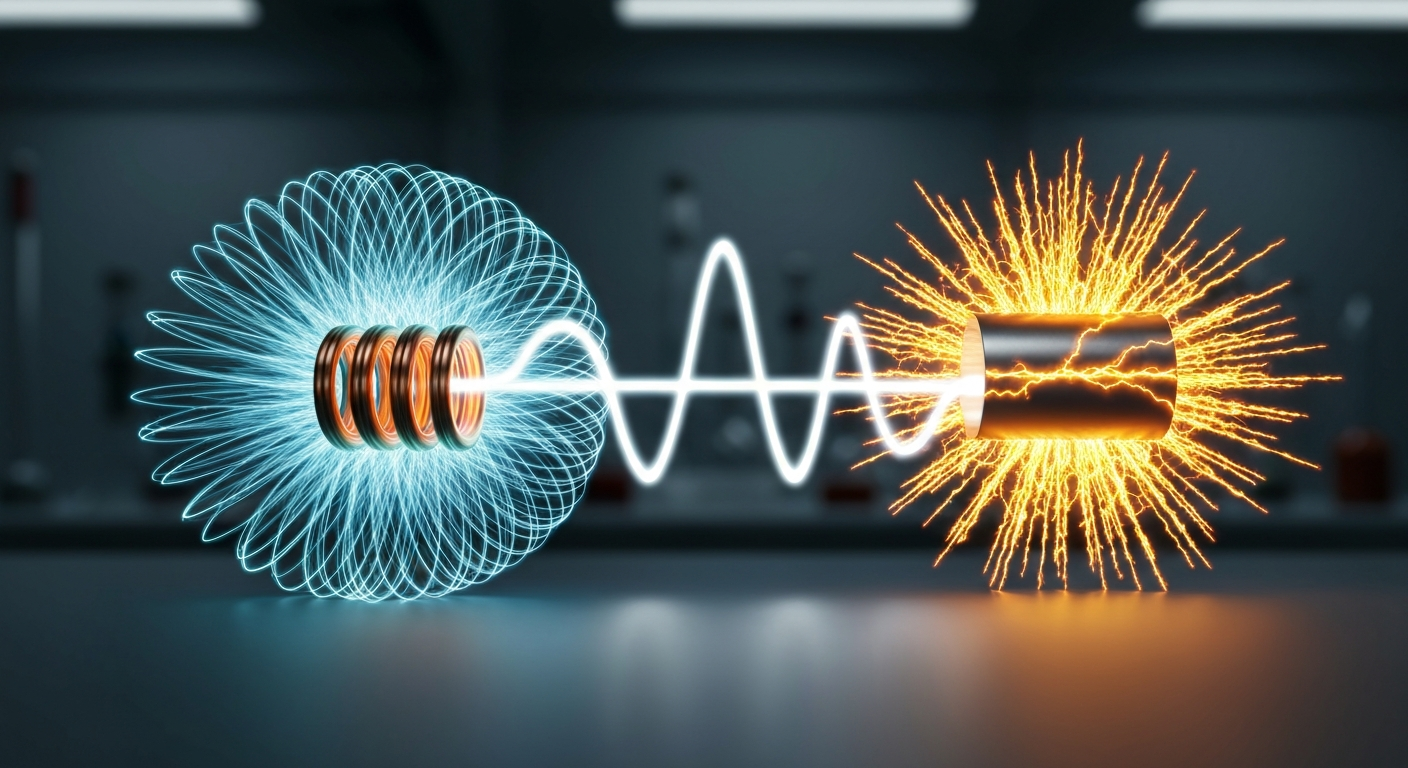

Reactance is the opposition to the flow of an alternating current (AC) as a result of a circuit’s inductance or capacitance. Unlike electrical resistance, which dissipates energy as heat, reactance stores energy in a magnetic or electric field and returns it to the circuit later in the cycle. Measured in ohms (Ω), reactance is a crucial component of a circuit’s total opposition to current, known as AC impedance (Z). There are two distinct types: inductive reactance (XL), which comes from inductors (like coils in motors and transformers), and capacitive reactance (XC), which comes from capacitors. Understanding the interplay between these two forces is fundamental to analyzing AC circuits, correcting power factor, and ensuring the proper function of modern electrical systems.

The Core Difference: Reactance vs. Resistance

While both resistance and reactance are measured in ohms and oppose the flow of current, they function very differently. Resistance is present in both AC and DC circuits, like those in a simple DC motor direct current system, and it always opposes current flow by converting electrical energy into heat. You can learn more about the fundamental differences in our guide to AC vs. DC current.

Reactance, however, only exists in AC circuits. It arises because of the constantly changing direction and magnitude of the current and voltage. Instead of dissipating energy, reactive components store it temporarily in a field—a magnetic field for inductors and an electric field for capacitors—and then release it back into the circuit. This storage and release process creates an opposition to the change in current or voltage, causing a phase shift between them. The total opposition in an AC circuit, which is a combination of resistance and reactance, is called AC impedance (Z).

Understanding the Two Types of Reactance

Reactance comes in two opposing forms: inductive and capacitive. Nearly all complex AC circuits contain some combination of both.

Inductive Reactance (XL): The Opposition from Inductors

Inductive reactance (XL) is the opposition to current caused by an inductor. Inductors, which are essentially coils of wire, are core components in devices like an electrical transformer, motors, and solenoids. When AC flows through an inductor, the oscillating current generates a constantly changing magnetic field. This changing field, in turn, induces a voltage (called a “counter-electromotive force” or back-EMF) in the coil that opposes the original flow of electric current. This opposition is XL.

The formula for inductive reactance is:

XL = 2πfL

Where:

- XL is the inductive reactance in ohms (Ω).

- f is the frequency of the AC signal in hertz (Hz).

- L is the inductance of the coil in henries (H).

This formula shows that XL is directly proportional to both frequency and inductance: if either increases, inductive reactance increases. This is a key principle in understanding leading vs lagging current. In an inductive circuit, the voltage peaks before the current does. This relationship is easily remembered with the mnemonic ELI the ICE man. The “ELI” part signifies that in an inductor (L), voltage (E) comes before current (I).

Capacitive Reactance (XC): The Opposition from Capacitors

Capacitive reactance (XC) is the opposition to current caused by a capacitor. A capacitor stores energy in an electric field between its plates. In an AC circuit, the capacitor is continuously charging and discharging as the voltage alternates. This constant change in stored charge opposes the change in voltage, which in turn impedes the flow of current. This opposition is XC.

The formula for capacitive reactance is:

XC = 1 / (2πfC)

Where:

- XC is the capacitive reactance in ohms (Ω).

- f is the frequency of the AC signal in hertz (Hz).

- C is the capacitance in farads (F).

Unlike XL, capacitive reactance is inversely proportional to frequency and capacitance. If frequency or capacitance increases, XC decreases. This brings us to the “ICE” part of ELI the ICE man: in a capacitor (C), current (I) comes before voltage (E). The current must flow to the capacitor’s plates first to build up the charge that creates the voltage across it.

How Reactance Combines: Series and Parallel Reactance

When a circuit contains both inductors and capacitors, their reactances interact. Because their effects are opposite—one causes current to lag voltage, and the other causes it to lead—they effectively cancel each other out.

Reactance in a Series Circuit

In a series circuit, the total reactance (X) is the simple difference between inductive and capacitive reactance:

X_total = XL - XC

- If XL is greater than XC, the circuit is net inductive, and the total current will lag the total voltage.

- If XC is greater than XL, the circuit is net capacitive, and the total current will lead the total voltage.

The total opposition, or AC impedance (Z), is then found by combining the total reactance and the resistance using the Pythagorean theorem, often visualized with the impedance triangle.

Z = √(R² + X_total²) = √(R² + (XL - XC)²)

Reactance in a Parallel Circuit

In a parallel circuit, calculating total reactance and impedance is more complex, as it involves working with the reciprocals of resistance and reactance. However, the core principle remains the same: inductive and capacitive reactances still work to cancel each other out. The overall behavior of the circuit (whether it’s net inductive or capacitive) depends on which of the two reactive currents is larger.

Practical Implications for the Journeyman Electrician

Understanding reactance isn’t just theory; it has daily, practical consequences in the field. From power quality to motor performance, reactance is a key factor a journeyman electrician must manage.

Power Factor and Power Factor Correction

One of the most important applications of reactance theory is power factor correction. Most industrial facilities have many motors, which are highly inductive loads. This causes the current to lag the voltage, resulting in a poor power factor. A low power factor means that for the same amount of useful work (true power, in kW), more total current (apparent power, in kVA) must be drawn from the utility. This inefficiency leads to higher energy losses, and many utilities charge a power factor penalty or otherwise incentivize improving power factor.

To combat this, electricians install banks of capacitors. The capacitive reactance (XC) from the capacitors directly counteracts the inductive reactance (XL) from the motors. By generating leading reactive power (measured in kVAR), the capacitors cancel out the lagging reactive power, bringing the overall power factor closer to unity (1.0) and improving the system’s efficiency. This is a common field of work—installing and tuning power factor correction equipment is routine in many industrial facilities due to energy efficiency goals, utility incentives, and the operational need to reduce apparent power and improve system capacity.

VFDs, Non-Linear Loads, and Harmonic Distortion

Modern devices like a Variable Frequency Drive (VFD), LED lighting, and EV chargers are known as non-linear loads. Unlike simple motors, they don’t draw current in a smooth sinusoidal wave. Instead, they draw it in pulses, which introduces unwanted frequencies—or harmonic distortion—back into the power system. A VFD controls motor speed by altering the frequency, which directly changes XL and XC, adding another layer of complexity. These harmonics are integer multiples of the fundamental frequency; on a 60 Hz system common problematic harmonics are the 3rd (180 Hz), 5th (300 Hz) and 7th (420 Hz). These harmonic currents can increase heating, contribute to nuisance tripping, and stress equipment because reactance and impedance change with frequency.

Other Real-World Effects: Voltage Drop and Skin Effect

Two other phenomena are critical for electricians to understand:

- Voltage Drop Calculation: In DC circuits, voltage drop is simply a product of current and resistance (V=IR). In AC circuits, however, a proper voltage drop calculation must use impedance (V=IZ), accounting for both resistance and reactance. On long conductor runs, inductive reactance can contribute significantly to voltage drop, potentially requiring larger conductors to ensure equipment operates correctly.

- Skin Effect: At higher frequencies, AC tends to flow only on the outer surface, or “skin,” of a conductor. This reduces the effective cross-sectional area of the wire, increasing its effective AC resistance. The skin effect is caused by eddy currents induced within the conductor itself—a direct consequence of the changing magnetic fields central to reactance.

Understanding these concepts is vital for any professional electrician. Master the principles of AC circuits. Sign up for our online electrical courses.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the main difference between reactance and resistance?

Resistance opposes both AC and DC current and dissipates energy as heat. Reactance only opposes AC current and temporarily stores energy in a magnetic (inductive) or electric (capacitive) field, causing a phase shift between voltage and current.

How does ELI the ICE man help explain leading vs lagging current?

This mnemonic is a memory aid for phase relationships. “ELI” means that for an inductor (L), voltage (E) leads current (I). “ICE” means that for a capacitor (C), current (I) leads voltage (E). It summarizes which quantity peaks first in reactive components.

Why is power factor correction so important in industrial settings?

Industrial settings use many large motors, which are inductive loads that cause a low, lagging power factor. This leads to energy inefficiency and financial penalties or utility incentives aimed at improving power factor. Power factor correction uses capacitors to counteract the inductive reactance, increasing efficiency and reducing apparent power requirements.

Can you have reactance in a DC motor direct current circuit?

No. Reactance is fundamentally a reaction to a change in current or voltage. In a steady-state DC motor direct current circuit, the current and voltage are constant, so there is no change to oppose. Therefore, inductors act like simple wires (short circuits) and capacitors act like open circuits, and neither exhibits reactance.

How is total reactance calculated in a series circuit?

In a series vs parallel circuit, the rules differ. For a series circuit, total reactance (X) is the difference between the inductive reactance (XL) and capacitive reactance (XC): X_total = XL – XC. The result determines if the circuit is net inductive or net capacitive.

Continuing Education by State

Select your state to view board-approved continuing education courses and requirements:

Disclaimer: The information provided in this educational content has been prepared with care to reflect current regulatory requirements for continuing education. However, licensing rules and regulations can vary by state and are subject to change. While we strive for accuracy, ExpertCE cannot guarantee that all details are complete or up to date at the time of reading. For the most current and authoritative information, always refer directly to your state’s official licensing board or regulatory agency.

NEC®, NFPA 70E®, NFPA 70®, and National Electrical Code® are registered trademarks of the National Fire Protection Association® (NFPA®)