Understanding Brake Fade and Proper Downhill Braking

Understanding Brake Fade: A Guide for Electrical Professionals

Understanding brake fade is crucial for safety and system longevity, not just in vehicles but also in the complex industrial systems that electricians manage. At its core, brake fade is the reduction in stopping power caused by excessive heat buildup in a braking system. This heat diminishes the friction needed to slow down, leading to potentially dangerous failures. For a journeyman electrician or master electrician, this principle extends beyond mechanical brakes into the realm of electrical braking. While not a standard industry term, we can think of improper energy dissipation in a Variable Frequency Drive (VFD)—which causes VFD overvoltage faults—as a form of “electrical brake fade.” (It is important to note that this is a conceptual analogy to explain a technical fault; “electrical brake fade” is not a defined NEC or industry standard term.) Solutions like dynamic braking resistors and braking chopper circuits are essential components in managing this energy. A comprehensive understanding of these concepts, often part of advanced electrician training and online electrical courses, is vital for designing and maintaining robust, high-performance motor control systems that handle high-inertia loads safely and effectively.

What is Mechanical Brake Fade? The Physics of Stopping

All braking systems, whether mechanical or electrical, are fundamentally about energy conversion. When a vehicle or machine is in motion, it has kinetic energy. To stop it, that kinetic energy must be converted into another form, most commonly thermal energy (heat). Mechanical brake fade occurs when the system’s components—pads, rotors, or fluid—get so hot that they can no longer effectively manage this energy conversion.

- Friction Fade: The brake pad and rotor materials overheat, causing a drop in the coefficient of friction. The brake pedal might feel firm, but the vehicle doesn’t slow down as it should. This is common during long downhill descents where brakes are applied continuously.

- Fluid Fade: The hydraulic fluid within the brake lines boils from the extreme heat. Since vapor is compressible and liquid is not, pressing the brake pedal compresses the vapor bubbles instead of actuating the brake calipers, leading to a spongy or “faded” pedal that goes to the floor with little effect.

This core problem—managing excess energy as heat—has a direct parallel in the world of electrical motor control, a critical area of expertise for electricians moving beyond residential work.

The Electrical Parallel: Understanding Brake Fade in Motors and Drives

For a modern electrician, especially a master electrician working in industrial settings, managing motors connected to high-inertia loads is a common task. Just as a heavy truck going downhill wants to speed up, a heavy industrial fan or conveyor belt, when told to stop, carries immense rotational inertia. Stopping it quickly requires the motor to absorb that energy. This is where electrical braking comes in, and where the risk of what can be analogized to “electrical brake fade”—that is, system faults due to excess energy—becomes a serious concern.

Regenerative Braking and its Limitations

Modern VFDs offer regenerative braking, where the motor acts as a generator, taking the load’s kinetic energy and converting it into electrical energy. In an ideal scenario, this power is fed back to the AC power line, saving energy. However, there are significant regenerative braking limitations. Standard VFDs that use an uncontrolled diode rectifier stage do not return power to the grid; only specialized regenerative or active-front-end VFDs are designed to push power back to the utility. In addition, returning power to the grid often requires compliance with utility interconnection and power-quality requirements such as standards that address harmonics and grid impact. When the motor generates more power than the VFD and its associated systems can absorb or dissipate, the excess energy raises the DC bus voltage. This results in one of the most common issues: VFD overvoltage faults, which trip the drive to protect its components. Conceptually, this is analogous to mechanical brake fade—the system is overwhelmed by energy and ceases to function correctly.

Dynamic Braking: The Solution for High-Inertia Load Braking

This is where dynamic braking provides a robust solution. Instead of trying to send excess energy back to the grid, dynamic braking diverts it to be dissipated safely as heat. This is achieved with two key components:

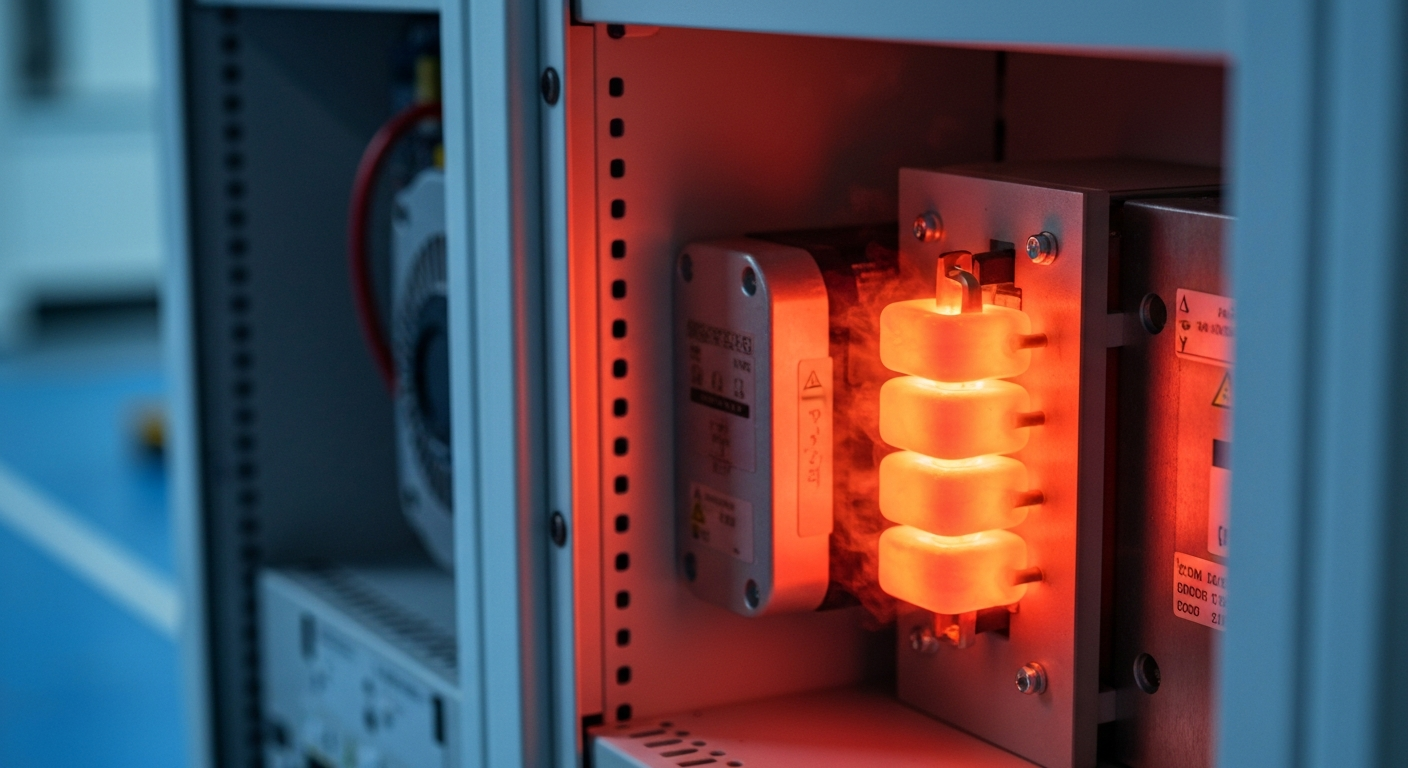

- Dynamic Braking Resistors: These are large resistors designed to handle high power. They essentially act as a “heating element” to burn off the excess electrical energy generated by the motor during braking. Proper braking resistor sizing is critical; a resistor that is too small will overheat and fail, while one that is too large may not dissipate energy fast enough. The duty cycle in braking resistors is another key parameter, indicating how long the resistor can handle a load before it needs to cool down.

- Braking Chopper Circuits: A braking chopper circuit is the intelligent switch that monitors the VFD’s DC bus voltage. When the voltage rises to a dangerous level during braking, the chopper rapidly turns on, diverting the current to the dynamic braking resistors. Once the voltage drops to a safe level, the circuit turns off. This process, also known as rheostatic brake control (a form of dynamic braking that dissipates power in a resistor), protects the drive from overvoltage faults and allows for powerful, controlled deceleration of high-inertia loads. This precise control is essential for proper inverter thermal management.

Advanced Braking Technologies and Principles

Beyond dynamic braking, several other methods are used in specialized applications. A well-rounded electrician should be familiar with these principles, which often appear in advanced curricula like the NCCER Industrial Electrician Level 4 curriculum and other professional electrician training.

Electromagnetic and Other Braking Methods

Some systems use non-friction or purely electrical methods for braking. An eddy current brake, for example, uses a magnetic field to induce electrical currents (eddy currents) in a rotating disc. These currents generate their own opposing magnetic field, creating braking force. However, like any system converting motion to heat, they are susceptible to eddy current brake overheating if not designed for the thermal load. Other methods include:

- DC Injection Braking: This technique involves injecting DC voltage into the windings of an AC motor after the AC power is removed. This creates a stationary magnetic field that the rotor resists turning through, bringing it to a rapid stop. It generates significant heat within the motor itself and is typically used for infrequent stopping or holding applications.

- Motor-Generator Braking Principles: In large-scale legacy systems, a motor-generator set can be used for braking. The primary motor, now acting as a generator, drives a separate motor that returns power to the line or dissipates it.

- Electromagnetic Retarder Maintenance: Common in heavy transport applications like trucks, buses, and rail systems, retarders are a form of eddy current brake integrated into the driveline. Proper electromagnetic retarder maintenance is crucial to ensure they can handle the thermal load without failing.

Practical Application: Calculations and Troubleshooting

A key skill for a journeyman electrician or master is translating theory into practice. This includes performing necessary calculations and diagnosing system failures.

Step-by-Step Guide to Braking Torque Calculation

While precise formulas can be complex, understanding the conceptual steps for braking torque calculation is essential for system design. This knowledge goes beyond what a typical residential electrician might need but is fundamental for industrial roles.

- Determine the Load Inertia: Calculate or find the total inertia of the motor’s rotor and the connected load (e.g., flywheel, fan, or drum). This is the ‘mass’ you need to stop.

- Define the Braking Requirement: Establish the desired stopping time. Stopping a heavy load in 3 seconds requires far more torque than stopping it in 30 seconds.

- Calculate the Required Torque: Use the formula Torque = Inertia x Angular Deceleration (e.g., Torque in Newton-meters (N·m), Inertia in kg·m², and Angular Deceleration in rad/s²). This gives you the braking torque needed from the motor.

- Factor in Friction and Losses: Add any system friction that helps with braking and subtract any forces (like gravity on a hoist) that work against braking.

- Select the Braking System: Based on the required torque and braking frequency, determine if the motor’s natural ability, regenerative braking, or a dynamic braking system is required. This calculation directly informs braking resistor sizing.

Key Considerations for Electric Brake Controller Troubleshooting

When a VFD or braking system fails, a systematic approach is key. Effective electric brake controller troubleshooting involves checking several key areas:

- Check for Fault Codes: The VFD is your first source of information. An overvoltage fault points directly to a problem with energy dissipation.

- Inspect the Braking Resistor: A common point of failure. Check for an open circuit (burned out) or incorrect resistance value. Ensure it is correctly sized for the application.

- Verify Chopper Circuit Operation: Ensure the braking chopper is turning on at the correct DC bus voltage. This may require monitoring the voltage and the chopper output with an oscilloscope.

- Review VFD Parameters: Check that the VFD is programmed correctly to enable the dynamic braking circuit and that the voltage setpoints are correct. Incorrect settings can prevent the chopper from ever activating.

- Assess the Application: Has the load increased? Is the braking duty cycle more demanding than the system was designed for? Sometimes the system is working correctly but is simply undersized for a new task.

A thorough understanding of these principles, often covered in detail through online electrical courses, is what separates a parts-changer from a true diagnostics expert. It all comes back to the fundamental concepts found in resources like the NEC code book, specifically NEC Article 430 for motors and controllers, which prioritizes safety through proper equipment installation and thermal management. Part X of Article 430 (Adjustable-Speed Drive Systems) specifically addresses power conversion equipment and braking in VFD applications; Part VII covers motor controllers more generally.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- What is the primary cause of brake fade?

- The primary cause of brake fade is excessive heat. In mechanical systems, heat reduces the friction between pads and rotors. In electrical systems like VFDs, excess kinetic energy converted to electricity causes a voltage spike (VFD overvoltage fault) when it cannot be dissipated quickly enough, effectively “fading” the braking capability.

- How do dynamic braking resistors prevent VFD overvoltage faults?

- Dynamic braking resistors provide a path for excess electrical energy to be converted into heat. When a braking chopper circuit detects that the VFD’s internal DC bus voltage is rising to a dangerous level, it diverts that electrical energy to the resistor, which dissipates it as heat, thus preventing the VFD from tripping on an overvoltage fault.

- What is the difference between regenerative and dynamic braking?

- Regenerative braking attempts to capture the braking energy and return it to the power source for reuse, increasing efficiency. Dynamic braking does not reuse the energy; it dissipates the braking energy as heat through a resistor. Dynamic braking is used when regenerative braking is not feasible or when the amount of energy is too great for the power source to absorb.

- Why is braking torque calculation important for a master electrician?

- A master electrician is often responsible for designing, specifying, or commissioning complex motor control systems. Accurate braking torque calculation is essential to ensure the system can safely and reliably control its load, preventing mechanical damage or safety hazards. It directly impacts the selection and sizing of the VFD, motor, and any required dynamic braking components.

- What kind of electrician training covers these advanced topics?

- Advanced electrician training programs, continuing education courses for license renewal, and specialized certifications like the NCCER Industrial Electrician Level 4 curriculum cover motor controls, VFDs, and braking principles. These topics are crucial for any electrician looking to work in industrial automation, manufacturing, or maintenance environments.

Continuing Education by State

Select your state to view board-approved continuing education courses and requirements:

Disclaimer: The information provided in this educational content has been prepared with care to reflect current regulatory requirements for continuing education. However, licensing rules and regulations can vary by state and are subject to change. While we strive for accuracy, ExpertCE cannot guarantee that all details are complete or up to date at the time of reading. For the most current and authoritative information, always refer directly to your state’s official licensing board or regulatory agency.

NEC®, NFPA 70E®, NFPA 70®, and National Electrical Code® are registered trademarks of the National Fire Protection Association® (NFPA®)