True Power vs. Apparent Power: A Guide to Power Factor

True Power vs. Apparent Power: A Guide to Power Factor

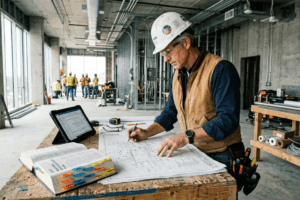

For any working journeyman electrician or master electrician, understanding the nuances of AC power is fundamental. The relationship between true power vs apparent power is at the heart of energy efficiency, system design, and utility billing. In simple terms, True Power (measured in kilowatts, kW) is the power that performs actual work, like lighting a lamp or turning a motor shaft. Apparent Power (measured in kilovolt-amperes, kVA) is the total power supplied by the utility, which includes both the working power and non-working “reactive” power. The ratio between these two is called Power Factor. A low power factor signals inefficiency, often caused by inductive loads like motors and transformers, leading to higher currents and costly demand charges from the utility. Mastering this concept is crucial for optimizing electrical systems and reducing operational costs.

What is True Power (kW)?

True Power, also known as Real Power or Working Power, is the energy that is consumed by a circuit to perform useful work. Think of it as the power that directly translates into an intended output—heat from a resistive heater, light from a bulb, or torque from a motor. It is measured in watts (W) or, more commonly for larger systems, kilowatts (kW).

Resistive loads are the most straightforward consumers of true power. In a purely resistive circuit, such as one with incandescent lighting or electric heating elements, the voltage and current waveforms are in phase. This means they rise and fall together, and all the power delivered by the source is converted into work. In this ideal scenario, the true power is equal to the apparent power, resulting in a perfect power factor of 1.0.

Understanding Apparent Power (kVA) and Reactive Power (kVAR)

Apparent Power is the total power that the utility must generate and transmit to your facility. It is the vector sum of true power and reactive power and is measured in volt-amperes (VA) or kilovolt-amperes (kVA). This is the value used to size transformers, generators, and wiring because it represents the total current the system must handle, regardless of how much work is actually being done.

The component that creates the difference between apparent and true power is Reactive Power (Q). Measured in volt-amperes reactive (VAR) or kilovolt-amperes reactive (kVAR), this is the “wattless” power required to create and sustain the magnetic fields in inductive loads like motors, solenoids, and every electrical transformer. This power doesn’t perform useful work but circulates between the source and the load, increasing the total current on the system. While necessary for operation, excessive reactive power leads to inefficiency and financial penalties.

The Power Triangle: Visualizing the Relationship

The relationship between these three types of power is best visualized using the power triangle, a right-angle triangle that provides a clear graphical representation for any AC circuit.

- True Power (kW) forms the adjacent side of the triangle, representing the work-performing power.

- Reactive Power (kVAR) forms the opposite side, representing the non-working power stored in magnetic or electric fields.

- Apparent Power (kVA) is the hypotenuse, representing the vector sum of true and reactive power.

The angle between the true power and apparent power sides is known as the phase angle (theta, θ). The cosine of this angle is the Power Factor. A larger phase angle indicates higher reactive power and a lower, less efficient power factor.

What is Power Factor and Why Does It Matter?

Power factor (PF) is the ratio of True Power (kW) to Apparent Power (kVA). It’s a number between 0 and 1 that measures how effectively electrical power is being used. A power factor of 1.0 (or 100%) means all power is being used for work (kW = kVA). A power factor of 0.8 means only 80% of the supplied power is doing work, with the rest being non-productive reactive power.

A low power factor is problematic for several reasons:

- Higher Utility Bills: Many utilities impose demand charges or penalties for customers with power factors below a certain threshold (often 0.90 or 0.95) to compensate for the extra generating and transmission capacity their inefficient loads require.

- Reduced System Capacity: Higher reactive power means higher overall current (amperage) for the same amount of work. This increased current can overload circuits, transformers, and switchgear, reducing the available capacity of your entire electrical system.

- Increased Voltage Drop: Higher current flowing through conductors leads to greater voltage drop, which can impair the performance and lifespan of equipment. Professionals often use a voltage drop calculator to ensure systems are designed to handle these loads without excessive drop.

- Energy Losses: The higher current also results in greater I²R (heat) losses in conductors and equipment, wasting energy and contributing to higher operating temperatures.

Understanding these impacts is essential for anyone dealing with industrial applications, especially when studying 480V 3-phase power systems where large motors are common.

A Practical Guide to Power Factor Correction

The process of improving a low power factor is known as Power factor correction. This is typically achieved by introducing capacitive loads to counteract the effect of inductive loads. Since capacitors generate reactive power that is 180 degrees out of phase with the reactive power consumed by inductors, they effectively cancel it out, reducing the overall apparent power and bringing the power factor closer to 1.0. Here is a step-by-step guide to implementing power factor correction:

- Measure and Analyze the System: The first step is to use a power quality analyzer to measure the existing power factor, load profile, and harmonic distortion. This data is crucial for determining the root cause of the poor power factor—typically large, lightly loaded induction motors.

- Calculate Required Correction: Based on the analysis, calculate the amount of capacitive reactive power (kVAR) needed to raise the power factor to a desired target, usually above 0.95 to avoid utility penalties. This involves using formulas derived from the power triangle and is a key skill for advanced electrical work, often covered in courses on three-phase electrical calculations.

- Select and Place Capacitors: Correction can be applied at different points. Centralized correction involves installing one large capacitor bank at the main service entrance. Decentralized correction places banks at motor control centers. Local correction involves installing capacitors directly at the terminals of large motors, often controlled by a motor-rated switch.

- Install Equipment per NEC Guidelines: Installation of capacitor banks must comply with the NEC code book, specifically Article 460. This article outlines requirements for conductor sizing (which must have an ampacity of at least 135% of the capacitor’s rated current), overcurrent protection, and safe discharge of stored energy. Per NEC 460.9, if capacitors are connected on the load side of a motor overload device, the relay setting must be adjusted based on the improved power factor.

- Verify Performance: After installation, use the power quality analyzer again to confirm that the power factor has improved to the target level and that no adverse effects, such as harmonic resonance, have been introduced.

Mastering these calculations is key for any electrician looking to advance their career. Improve system efficiency by mastering power factor. Explore our online electrical courses to deepen your expertise.

The Role of VFDs and Other Loads

Modern equipment like a Variable Frequency Drive (VFD) can have a complex effect on power factor. A VFD itself typically presents a high power factor to the line (often 0.95 or better) because its internal DC bus capacitors supply the reactive power needed by the motor. This can significantly improve the displacement power factor of the motor it controls, especially when the motor is lightly loaded. However, VFDs also introduce harmonic distortion, which can affect the true power factor if not properly filtered.

Understanding different load types is foundational. While inductive loads cause a lagging power factor, capacitive loads cause a leading one. The principles of how these components behave in AC circuits are rooted in basic electrical theory, including the difference between a series vs parallel circuit and how impedance affects current flow.

Even an electrical transformer contributes to poor power factor. A transformer, especially one that is energized but lightly loaded, draws magnetizing current which is almost purely reactive, degrading the system’s overall power factor. This is a critical consideration in facilities with multiple 3-phase transformer configurations.

Key Takeaways for Electricians

- True Power (kW) is the “working” power that gets the job done.

- Apparent Power (kVA) is the “total” power supplied by the utility, which conductors and transformers must be sized to handle.

- Power Factor is the ratio of kW to kVA, representing system efficiency.

- Inductive Loads like motors and transformers are the primary cause of poor (lagging) power factor.

- Power Factor Correction uses capacitors to counteract inductive loads, lowering utility bills and increasing system capacity.

- The NEC code book provides specific rules in Article 460 for safely installing capacitor banks.

Continuing Education by State

Select your state to view board-approved continuing education courses and requirements:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

- 1. What is the simplest way to explain true power vs apparent power?

- Think of a glass of beer. The beer itself is the True Power (kW)—what you actually want and use. The foam on top is Reactive Power (kVAR). The entire contents of the glass, beer plus foam, is the Apparent Power (kVA). You pay for the whole glass, so you want as little foam as possible. A good power factor means more beer and less foam.

- 2. Why do utilities issue penalties for low power factor through demand charges?

- A low power factor means your facility is drawing more current than necessary to do the same amount of work. This higher current puts a greater strain on the utility’s entire infrastructure—their generators, transformers, and power lines. The demand charges or penalties are to compensate the utility for this extra burden and to incentivize customers to improve their energy efficiency.

- 3. Can a Variable Frequency Drive (VFD) be used for power factor correction?

- Yes, in a way. A VFD improves the power factor of the motor system it controls by supplying the motor’s reactive current from its own DC bus capacitors, so the power line doesn’t have to. While the VFD itself has a very high power factor, it’s not typically installed solely for system-wide power factor correction like a capacitor bank would be. Its primary purpose is motor speed control.

- 4. How does an electrical transformer affect power factor?

- An electrical transformer requires magnetizing current to create its magnetic field, and this current is reactive. Therefore, a transformer is an inductive load that contributes to a lagging power factor. The effect is most pronounced when a transformer is energized but has little to no load connected to its secondary, as the power being drawn is almost entirely reactive.

Disclaimer: The information provided in this educational content has been prepared with care to reflect current regulatory requirements for continuing education. However, licensing rules and regulations can vary by state and are subject to change. While we strive for accuracy, ExpertCE cannot guarantee that all details are complete or up to date at the time of reading. For the most current and authoritative information, always refer directly to your state’s official licensing board or regulatory agency.

NEC®, NFPA 70E®, NFPA 70®, and National Electrical Code® are registered trademarks of the National Fire Protection Association® (NFPA®)