The Dangers of an Improperly Wired Multi-Wire Branch Circuit

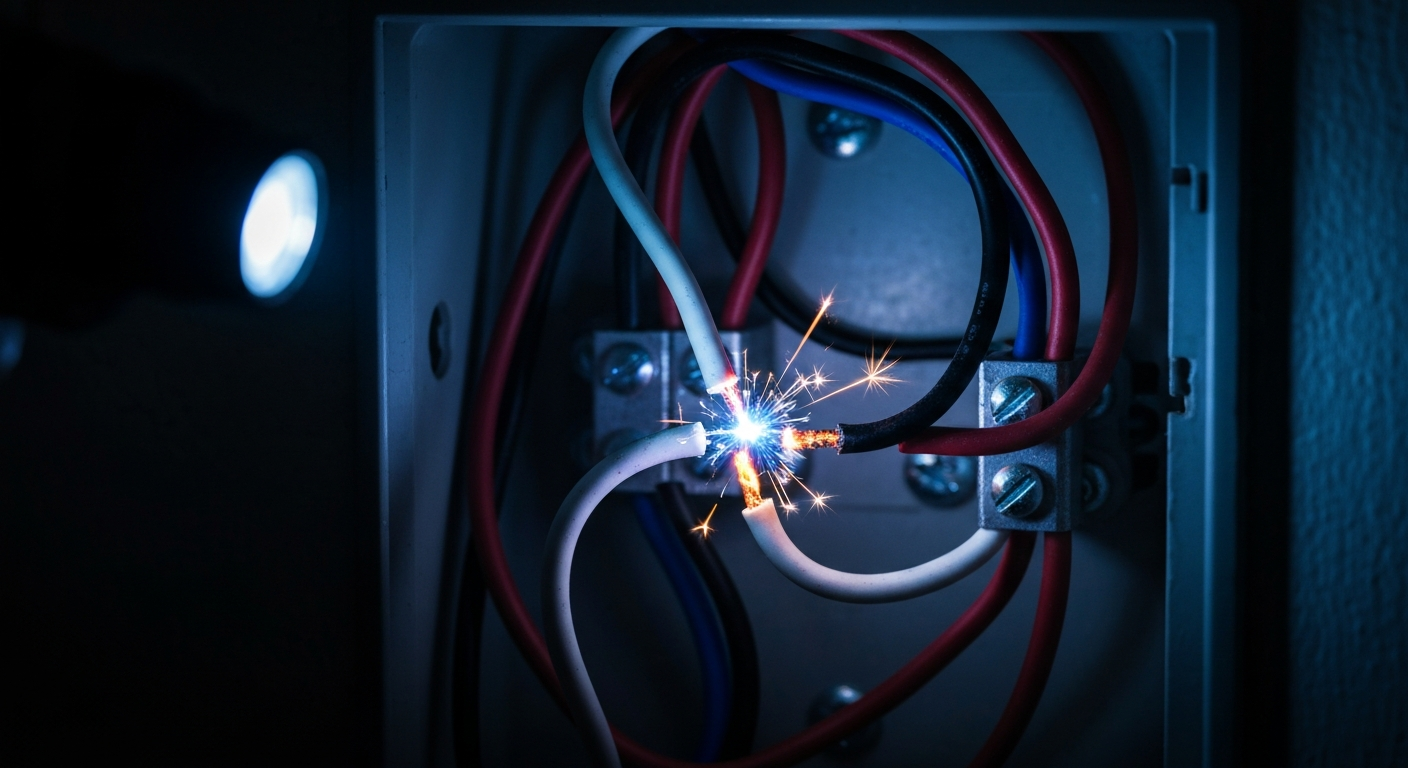

The Unseen Threat: Exposing the Dangers of Improperly Wired Multi-Wire Branch Circuits

Walk onto a residential job site from a few decades ago, and you’re likely to find them: multi-wire branch circuits (MWBCs). For years, running a shared neutral circuit was a common, cost-saving practice. It reduced wire, saved space in conduits, and was perfectly acceptable. But in today’s electrical landscape, that once-common practice is viewed with a heavy dose of caution. The rise of sophisticated safety devices and a deeper understanding of potential hazards have cast a long shadow over MWBCs. While they are still permitted by the National Electrical Code (NEC), the margin for error is razor-thin, and the consequences of a mistake can be catastrophic. Electrical failures are a significant factor in home fires, making a thorough understanding of these circuits more critical than ever for professional electricians.

What Exactly is a Multi-Wire Branch Circuit?

A multi-wire branch circuit, as defined in NEC 210.4, consists of two or more ungrounded (hot) conductors that share a single grounded (neutral) conductor. In a typical 120/240V single-phase system, this means a single 3-wire cable (plus ground) can do the work of two 2-wire cables. The key to a safe MWBC is that the two ungrounded conductors must be connected to different phases, or legs, at the panel. When this is done correctly and the line-to-neutral loads are reasonably balanced, the current on the shared neutral is only the difference between the currents on the two hot legs. If the loads are perfectly balanced, the neutral current is zero. This elegant efficiency is precisely why they were popular, but it’s also the source of their most significant dangers.

The Core Dangers: When a Shared Neutral Circuit Turns Hazardous

When installed perfectly, an MWBC is safe. However, incorrect installation or modification can quickly create severe risks of fire and electric shock. The most critical multiwire branch circuit dangers stem from a compromised neutral or improper phasing.

The Nightmare Scenario: Open Neutral Hazards

The single most dangerous failure in an MWBC is an open or lost neutral connection. If the shared neutral wire breaks or becomes disconnected anywhere along the circuit, a catastrophic chain of events begins. The two 120V circuits instantly become a 240-volt series circuit, with the connected appliances and devices acting as the load between the two hot legs. This places 120V-rated equipment in a 240V path, causing severe overvoltage and undervoltage conditions. A device with lower resistance (like a simple incandescent bulb) will experience a surge of voltage far exceeding its rating, often destroying it instantly and creating a fire hazard. Meanwhile, a device with higher resistance on the other leg will be starved for voltage and fail to operate correctly. This is one of the most destructive open neutral hazards an electrician can encounter.

Unbalanced Loads and the Overloaded Neutral

Another severe hazard occurs if the ungrounded conductors are terminated on the same phase at the panel. Instead of canceling each other out, the currents on the neutral wire become additive. For example, if two 15-amp loads are running on circuits mistakenly landed on the same phase, the shared neutral could be forced to carry 30 amps—far exceeding the wire’s ampacity. This creates an overloaded neutral, which can melt the wire’s insulation and ignite surrounding combustible materials, all without ever tripping a circuit breaker, as neither hot leg is overloaded. The risk of these unbalanced loads turning into a fire hazard is a primary reason for the industry’s shift away from MWBCs in many applications.

The Shock Risk: Failure of Simultaneous Disconnection

For anyone performing a circuit breaker replacement or working on a receptacle, a live shared neutral poses a serious shock hazard. If an electrician shuts off only one of the single-pole breakers protecting an MWBC, the circuit they believe is de-energized can still have a live neutral. The neutral will carry the return current from the other, still-active circuit. If that electrician disconnects the neutral, their body could become the path to ground, resulting in a severe shock. To mitigate this, NEC 210.4(B) mandates a means for simultaneous disconnection of all ungrounded conductors. This is typically achieved with a 2-pole common trip breaker or two single-pole breakers connected with listed breaker handle ties. This ensures that turning off one circuit de-energizes all conductors in the MWBC.

Navigating Modern Code: AFCI/GFCI Protection for MWBCs

The complexity of MWBCs is magnified by modern requirements for arc-fault and ground-fault protection. Implementing AFCI/GFCI for MWBC installations is not as simple as with standard circuits.

A standard GFCI outlet cannot be used to protect downstream receptacles on a shared neutral circuit. The GFCI will sense an imbalance because the neutral current it’s monitoring doesn’t match its own hot conductor’s current (since the neutral is also carrying current from the other circuit), leading to nuisance tripping. The correct way to provide this protection is at the source, using a 2-pole GFCI breaker or 2-pole arc fault breaker that is specifically designed for MWBCs. This ensures both hot legs and the shared neutral are monitored correctly. When installing devices on an MWBC, it’s also critical to use pigtailing neutrals in each outlet box rather than passing the neutral through the device terminals. This prevents the downstream portion of the neutral from being broken if a receptacle is removed. The equipment grounding conductor remains a separate, crucial safety path in all scenarios.

Best Practices and the Industry Shift

Given the risks and complexities, there’s a clear trend away from using MWBCs, especially in residential settings. The minimal cost savings on wire are often outweighed by the increased labor, the higher cost of 2-pole AFCI/GFCI breakers, and the significant potential for life-threatening errors. Statistics from the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) show that wiring and related equipment account for a majority of electrical distribution home fires, underscoring the need for safe and straightforward installation practices.

A deep understanding of the code is the best defense against these hazards. Staying current with NEC updates is non-negotiable for professional electricians who want to ensure every installation is safe and compliant. For a deeper dive, understanding how the 2023 NEC improves electrical worker safety is critical. This focus on safety isn’t just about code compliance; it’s about job site practice. To further enhance your safety protocols, learn more about how NFPA 70E updates have changed job safety planning.

Conclusion: Prioritizing Safety Over Savings

While multi-wire branch circuits are not prohibited by the NEC, they belong to a category of electrical work where “good enough” is a recipe for disaster. The potential for open neutral hazards, an overloaded neutral from improper phasing, and severe shock risks demand the highest level of care and expertise. For today’s professional electrician, the safest and often simplest approach is to dedicate a neutral for every branch circuit, eliminating the inherent dangers of shared neutrals altogether. As the industry continues to prioritize safety, the MWBC may become an even rarer sight on new installations.

Ready to sharpen your code knowledge and stay ahead of industry trends? Browse our courses at ExpertCE and ensure your skills are up-to-date.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Can you use a GFCI outlet on a multi-wire branch circuit?

It’s highly problematic. A standard GFCI receptacle will likely nuisance trip because it cannot correctly balance the shared neutral current. The code-compliant method is to use a 2-pole GFCI breaker at the panel. - What is the main danger of a shared neutral circuit?

The most severe danger is an open neutral, which can create a 240-volt series circuit across 120V devices, causing overvoltage that destroys equipment and creates a significant fire risk. - Does the NEC still permit multi-wire branch circuits?

Yes, NEC 210.4 still allows MWBCs, but with strict rules, including the requirement for a means of simultaneous disconnection for all ungrounded conductors.

Disclaimer: The information provided in this educational content has been prepared with care to reflect current regulatory requirements for continuing education. However, licensing rules and regulations can vary by state and are subject to change. While we strive for accuracy, ExpertCE cannot guarantee that all details are complete or up to date at the time of reading. For the most current and authoritative information, always refer directly to your state’s official licensing board or regulatory agency.